Used in Buddhist rituals, the shining foil decorating pagodas is about 30 times thinner than a human hair.

Used in Buddhist rituals, the shining foil decorating pagodas is about 30 times thinner than a human hair.

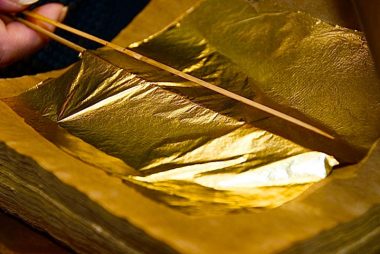

How thin is it?

Human skin is about .07 inches thick. The thickness of a sheet of paper is, on average, about .004 inches. By contrast, the hand-made gold leaf measures just .0001 inches thick. Three microns: about 30 times thinner than a human hair. It is like gilded spider webbing. Or barely materialized sunlight.

It must pound it 20,000 times to make it this thin. It takes more than five hours of hammering.

Gold leaf manufacture in Myanmar is many centuries old. It is associated closely with Buddhist ritual. Pasting gold leaf onto statues at pagodas is one way to honor the Buddha’s teachings. Gilding such figures is, according practitioners of Buddhism, “an act of loving kindness” and a path to “transfer good merits.” Gold in Buddhism signifies the sun: a flame of purity, knowledge, enlightenment.

Rows of shirtless young men swing seven-pound hammers at deer-hide satchels containing grains of gold stacked between layers of bamboo paper. They first strike the satchel in a circular pattern to flatten the gold into a coin-shaped disc. Then they smash the center of their targets to achieve maximum thinness. The gold grows hot from the thousands of blows. Time is kept with a clepsydra, an antique clock consisting of a coconut shell with a hole in it floating in a bucket of water. When it sinks every hour, the men take a 15-minute break.

Amid a steady thok-thok-thok of hammers, the coconut fills painfully slowly. It is not a profession for weak backs.

Gold leaf also can be eaten. It’s good for the heart. Ladies also put it on their faces as a cosmetic. Tourists used to buy gold leaf as a souvenir.

The Vatican drips with gold. The shrine of Al Aqsa, where Mohammed flew to heaven, is domed with gold. Almost every Hindu temple in India has its own gold reserve. (There are more than 4,000 tons of temple gold stashed across India, by one estimate, more than is hoarded in the vaults at Fort Knox.) From the very beginning, they offered gold to exalt gods and sages, yes, but also as a type of metaphysical collateral: down payment for a pleasant afterlife.

Some of the King Galon workshop’s gold leaf ends up on the 12-foot-tall, six-ton Buddha statue enshrined in Mahamuni Temple, Mandalay’s biggest pagoda.

The huge, shimmering, placid image sits encrusted with a lumpy coat of gold leaf that in places is six inches thick. Pilgrims, rich and poor, come and go from the shrine. Fragments of gold leafs product often glitter on their fingers.

Gold leaf is very difficult to remove from living skin.