Fool’s gold not completely worthless. There’s real gold inside. Scientists figure out how to squeeze real gold out of pyrite.

Fool’s gold not completely worthless. There’s real gold inside. Scientists figure out how to squeeze real gold out of pyrite.

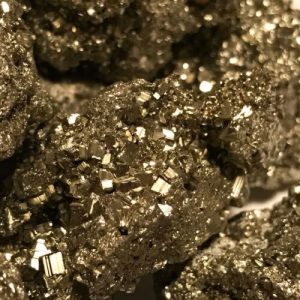

Would you be tricked into thinking these shiny nuggets of pyrite were real gold.

It turns out that fool’s gold may not be so useless after all. New research finds that the mineral, also known as pyrite, sometimes contains miniscule amounts of actual gold.

Alas, the gold hidden inside the shiny yellow mineral isn’t enough to make you a millionaire, but it could be enough to extract by industrial mining in a relatively environmentally friendly way.

“The discovery rate of new gold deposits is in decline worldwide with the quality of ore degrading, parallel to the value of precious metal increasing,” study leader Denis Fougerouse, an economic geologist at Curtin University in Australia, said in a statement.

Fool’s gold, or pyrite, is a mineral containing iron sulfate, made of iron and sulfur. It gets its name because it has fooled many a miner over the years.

Perhaps the biggest sucker taken in by pyrite was Sir Martin Frobisher, an English privateer and explorer who brought back 1,350 tons (1.1 million kilograms) of what he thought was gold ore to Queen Elizabeth in 1578, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia. Unfortunately for Sir Frobisher, the ore actually contained pyrite and a handful of other sparkly minerals-but no gold.

Yet pyrite and gold form in similar conditions, so pyrite can indicate that real gold is near. And pyrite crystals sometimes contain the occasional nanoparticle of real gold that gets caught up in the crystallization process, according to previous research..

The new study, however, has found a different form of gold hidden in pyrite.. Because pyrite is a crystal, that means its atoms are arranged in a neat, predictable pattern. But no crystal lattice is perfect, and Fougerouse and his colleagues found that gold can lurk in tiny defects in the pyrite’s crystal structure.

“The more deformed the crystal is, the more gold there is locked up in gold,” Fougerouse said in a statement. “The gold is hosted in nanoscale defects called dislocations-100,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair-so a special technique called atom probe tomography is needed to observe it.” Extracting the gold

Atom probe tomography uses electrical pulses to peel atoms from a sample and observe them one by one. The method destroys the gold threads. But Fougerouse and his team investigated ways to extract the tiny traces of gold from the pyrite without destroying them.

“Generally, gold is extracted using pressure oxidizing techniques (similar to cooking), but this process is energy hungry,” Fougerouse said. “We wanted to look into an eco-friendlier way of extraction.”

The researchers found they could remove the nanothreads of gold with a technique called selective leaching, in which a fluid dissolves the precious metal out of the sample without damaging the pyrite. They found that this worked well because the same tiny nooks that trap the gold also act as channels that help the dissolved gold travel out.